My Parole Officer says writing is still OK.^^

For the past decade or so I have written for various publications, primarily on issues related to Korea and Korean literature.

Below are some examples of that work.

Of course I like to think that I can write about anything.^^

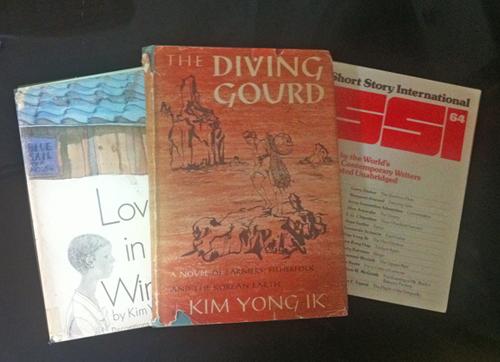

SEOUL, March 2 (Yonhap) — As an English saying goes, “Pioneers get arrows, while settlers get the land.” At this moment, as Korean literature expands overseas with authors such as Shin Kyung-sook, Kim Young-ha and Yi Mun-yol settling comfortably into magazines and onto best-seller charts, it is an auspicious time to look back at one of the bravest of all the Korean literary pioneers nearly forgotten, Kim Yong-ik.

Kim’s career writing in English began in 1957 and spanned nearly four decades. He published one book of folk tales, six novels, dozens of short stories, two essays, one television show and one movie (in Korea). He was published in The New Yorker, Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s Bazaar, Mademoiselle, and the Hudson Review among other magazines, had a book of short stories published, and was anthologized several times.

Kim wrote amusing stories for juveniles and penetrating and multi-layered works for adults. His influence went beyond the works he wrote; he also profoundly affected other authors. American poet Robert Bly once commented on Kim’s advice, saying, “I’ve been grateful for (it) for years.”

Yet, today, when we think of successful Korean authors in English, Kim Yong-ik’s name rarely comes up.

|

Kim Yong-ik teaching a class at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania |

Kim was also a skilled teacher. From 1957 to 1964, he taught at Ehwa Womans University and Korea University in Seoul. Kim also taught at the University of California, Berkeley as a visiting professor from 1972-1973 and then at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania from 1973-1990.

It is Kim’s writing that will leave a mark on history. Unfortunately, like most Asian writers of the era, Kim struggled to get out of the various pigeonholes English publishers and readers tried to place him in. The first edited collection of Asian-American work in the United States was published in 1972. The “Asian-American Authors” did not include South Korea as part of Asia, and consequently did not include any South Korean authors. Publishers often did not know exactly what to do with Kim, and looking back at the covers of his first novels is to recognize that regardless of content, publisher were trying to sell his works as juvenilia. Still, Kim persevered, and as time went by his works moved from being recognized as juvenile to adult.

Kim wrote with strong echoes of traditional Korean literature about diasporic states, a theme that would naturally have modern meaning for a Korean author steeped in memories of Japanese colonialization and the very real modern reality of a sundered nation. Many of Kim’s stories focused on relocation or dislocation, the experience of being physically moved to a foreign land or being psychically separated from one’s social milieu and second an eventual return to unity.

Kim wrote his first English short stories in 1957. “From Here You Can See the Moon” focused on a son returning to Korea and contained Kim’s first formal statement of his life-long theme of relocation as a process that eventually brings you back to where you begin — “The town is good enough for anyone to return to.”

The Diving Gourd (1962) was his first book and also strongly emphasizes physical displacement. In his early work we see characters that are sketches for the more complex characters that Kim later created. Early works were unanimously placed in Korea and featured only Koreans, but as Kim became more familiar with the U.S., his scope widened. Kim first addressed international topics in “They Won’t Crack It Open,” the first of three stories Kim located in the U.S. This work is still anthologized in some multicultural collections including Imagining America: Stories From the Promised Land and taught on university campuses across the English-speaking world.

Kim’s late-middle period featured a troika of works that revisited, often with a hard edge, themes of cyclical diasporism within and across cultures — “Moon Thieves” and the short stories “The Snake Man” and “The Sheep, Jimmy and I.”

His fiction also describes Kim’s personal path — from Korean village to internationally published author, and finally back home before his death.

That Kim was thematically “on the way back home” is demonstrated in the existing four-page fragment “Home Again (1945)” from his unfinished novel Gourd Hollow Dance. The narrator, Yang Ho, has been released from Japanese prison camp and returns home. Yang Ho explains how time spent in a prison cell in Japan has given him a vision of home, and the road home.

“Water Root in the rain, Water Root in the sun – the poplars against the sky – I was home again. In the Tokyo jail, scratches of fingernails, cracks in the cell well had turned into waving trees. Warm water in the throat, a little food, at such moments I saw in the scratches and cracks the road to the sky by Water Root.”

Kim’s wife, Kim Udam, in her elegy of the writer described Kim’s life as a process of departure leading to return to home and unity.

His shell is now resting at a sunny hillside family plot near his beautiful hometown.

He is now with his truly beloved.

Even today, Kim is not much known as a member of the Asian-American literary canon. One absence may stand in for many in this regard; Kim is absent from Asian American Short Story Writers: An A-To-Z Guide (Huang and Nelson), which is a work dedicated to collecting biographical information on all important Asian-American authors.

|

Why is it that this pioneer is forgotten? It is because Kim advanced to the beat of his own drummer. In his early years as an author Kim wrote fiction that focused on Korea and Korean issues in a language whose speakers did not know of Korea and/or Korean issues. In his later career, always the iconoclast, Kim continued to stand alone, often refusing to identify himself as an Asian, Asian-American, or Korean-American writer.

In his interview and writings, Kim repeatedly tried to make the point that his work was consciously outside of any “group.” Kim once famously said, “Am I Asian American? It depends on how you interpret ‘America.’ I write about minorities and forgotten people. I never think about Asian American. You know, I’m a little bit of a loner.” Kim, with his eyes solely on his literary task, was seldom concerned with appearances or labels.

The good news is that while Kim is not as well known as he should be, he continues to live on in universities across the world. Readers looking for the works of Kim Yong-ik can find two stories in Martha Foley’s Best American Short Stories, and six of his short stories are available online as PDFs on the Korea Journal web site. His short story Crown Dick was made into a PBS film after winning the PEN Syndicated Short Fiction Project in 1984.

A follower of Korean fiction, a follower of international fiction, in fact a follower of any and all fiction can only hope that the tremendous early contributions of Kim Yong-ik will someday get the recognition they deserve.

SEOUL, May 21 (Yonhap) — When asked to imagine early rappers, most people are hardly likely to conjure up the picture of a Korean man, dressed in humble clothes, sheltered from the rain by no more than a straw hat, walking across Korea with a staff and finding his lodging and food based on the wit, and sometimes ferocity, of his rhymes. And yet, the Korean poet who went by the name Kim Satgat could well be called the original rapper/battle-rapper.

Kim Satgat was born Kim Byeong-yeon in 1807 in what is now Yangju city in Gyeonggi Province, north of Seoul. His rather peaceful life was overturned when he was still a child, his entire clan disgraced after his grandfather was implicated in an uprising by discontented peasants, known as the Honggyongnae insurrection.

Kim and his brother were taken to live, in semi-obscurity, in the house of a family servant. Eventually, Kim returned home, got married, and had a son. It was about that time that he embarked on the life of a wanderer. Some speculate that this was due to financial difficulties, but the more literary story is that his poetic skills caused him to enter a poetry contest that he won in which he accidentally attacked the memory of his grandfather. Ashamed of this impiety, he relegated himself to a life of wandering, wearing a wide-brimmed straw hat (called satgat in Korean) to hide his face in shame.

In either case, from that time on Kim Satgat lived the life of an outcast. His son tracked him down three times, but three times Kim managed to slip away.

The nomadic poet, however, left a trail of memorable lines. Often forced to rhyme for his dinner or lodging, he revealed his skill as perhaps the world’s first “battle-rapper.” When challenged, he would frequently respond with poems that meant one thing in Chinese (the language of literature at the time) and quite another thing, usually insulting, in Korean.

|

Playwright Ha Tae-hung and writer Yi Mun-yol memorialized the talent of Kim Satgat through their books. (Photos courtesy of Charles Montgomery) |

Once, challenged by a village schoolmaster to write a poem for his evening lodging, Kim faced a different kind of problem. The schoolmaster, intending to deny him lodging, challenged Kim to write a poem in which the first line ended in the unusual character, myok. Kim responded, “Of all possible rhymes how did you find myok?”

The schoolmaster, cruel and still intending to deny lodging, demanded the character myok also be used to conclude the second line. Kim responded, “The first was hard enough to find, much more this second myok.”

Once more, the schoolmaster requested a line concluding in myok.

“If a night’s lodging depends on this myok…”

The vindictive schoolmaster again asked for a line ending in myok and, predictably, Kim responded, “Maybe a rustic schoolmaster knows nothing else but myok?”

These are clever uses of myok, with the first usage using the character just as the schoolmaster does — as a character without any contextual meaning. Yet, as the poem continues the character has useful meanings in the poem:

Of all the possible rhymes how did you find (the character) myok?

The first was hard enough to find, much more the second to seek and find.

If a night’s lodging depends on this seeking and finding,

Maybe a rustic schoolmaster knows nothing else but (seeking and finding OR the character itself) myok?

The late Richard Rutt, a former missionary and a scholar of Korean studies, noted, “The insulting poems could be interpreted as symbols of the spirit of revolt that may be supposed to smoulder in the breast of every Korean, constrained as he is by a highly conventional society.”

Kim Satgat’s second amazing extemporaneous skill was to compose simultaneously in Korean and Chinese and it is here that his link to battle rap becomes explicit. Because the languages share sounds and words, it is possible to write a poem in one language that has an entirely different meaning in the other language. This is a tremendously complicated process, for each word and each sentence must make sense in both languages. The most famous of Kim’s “double entendre” poems was composed at a wedding at which Kim was apparently upset with the host. In Chinese, Kim wrote a semi-cliched piece of work (All translations here are by Richard Rutt):

The sky is wide, beyond imagination,

The flowers fall and the butterflies come no longer

Chrysanthemums bloom in the cold sand,

The shadows of their stalks lie on the ground,

The poet passes the waterside arbour

And slumps in drunken sleep under a pinetree.

The moon moves, the mountain shadows shift

The merchants return home with their gains

This is a rather flat reflection on the passage of time. But when read aloud and understood in Korean, the poem takes on an entirely different meaning:

There are spider’s web on the ceiling,

Bran is scorching on the stove:

There’s a bowl of noodles

And half a dish of soy sauce

Here are some puffed grain and cakes

Jujubes and a peach.

Get away you filthy hound!

How that privy stinks!

What was a series of bland cliches is turned into an attack on the hospitality and cleanliness of the host. This kind of dual-language improvisation is a remarkable skill, and one that is not much found elsewhere in literature. Kim’s fame as a wit is so great that clever verses of unknown origin are often attributed to him.

|

Prof. John Eperjesi of Kyung Hee University, who has studied the works of Kim Satgat, calls him a thetorical trickster. |

John Eperjesi, an assistant professor in the School of English at Kyung Hee University, notes, “Like all great MCs, Kim Satgat was a rhetorical trickster who used humor, puns, irony and repetition to defeat his opponents. And the stakes were sometime high. In one battle, the losing poet had to have a tooth pulled out. It’s fortunate that Kim had good linguistic skills or he might have been remembered as the toothless poet.”

Kim was capable of lesser tricks as well; he sometimes wrote poetry in which the shape of Korean letters gave the poem meaning:

Stick a K in your belt.

Put NG in your ox’s nose

Go home and wash your R,

Or else you’ll dot your T

When the shapes of the Korean letters are taken into account, the poem becomes clear. The Korean letter K is shaped like a sickle [ㄱ], NG is a circle [ㅇ], R [ㄹ] is the same as the Chinese character for self, and T [ㄷ] needs only the addition of a dot at the top to become the Chinese character for death. So the poem goes something like:

Stick a sickle in your belt.

Put a ring in your ox’s nose

Go home and wash yourself

Or else you will die.

That example might not reach to the heights of poetry, but Kim was also capable of achieving sublime effects. Korean poetry often includes repetition and the following verse takes advantage of that:

White sand, white gulls, all white, so white,

I cannot tell white gulls from sand

A fisherman sings out, and away they fly:

Now I see the sand is sand and the gulls are gulls.

Kim Satgat has been memorialized in literature as well as history. In 1969, playwright Ha Tae-hung published a play entitled “The Life of the Rainhat Poet,” which follows Kim Satgat’s life from his early understanding of his compromised position in society to his eventual death. Kim was also memorialized by one of South Korea’s most internationally well-known writer, Yi Mun-yol, in his 1992 novel “The Poet.”

(Seoul Magazine, DECEMBER 19, 2016) Han Kang’s ‘Human Acts’ examines the human impact of one of modern Korea’s most painful episodes

The human body has often served as the canvas of history. It both writes history and has history inscribed upon it. Han Kang’s “Human Acts” contemplates the role of the human body during and after the Gwangju Uprising. The novel is a work of wide scope and breathtaking if occasionally harrowing storytelling. “Human Acts” is the translated follow-up to Han’s Booker Prize-winning “The Vegetarian,” and it is every bit as compelling and powerful as that predecessor.

A new take on an old form

The novel is presented from the perspectives of multiple narrators across six chapters (acts). The chapters revolve around the death of a Korean boy named Dong-ho. Han approaches yeonjak soseol (linked novel) here, a traditional Korean approach to modern fiction in which separately published short stories on a particular theme are read as a novel. Han’s focus on particular historical and social issues is also related to overarching elements of modern Korean fiction, which include being intensely focused on actual Korean experience as well as including didactic or hortatory elements. This has been an element of Korean modern fiction since it began at the turn of the 20th century. One of Han’s skills, however, is to leave the didactic and hortatory elements to express themselves indirectly through stark descriptions, actions and interpretation.

A meditation on death, survival and guilt

“Human Acts” starts with a young boy worrying about impending rain. The reason for his worry, however, is tragic. He is working in a makeshift morgue and he is afraid the rain will accelerate the decay of the corpses that surround him. The corpses are the human remains of victims of the Gwangju Uprising. Making this quick shift of tone, Han turns “Human Acts” into a meditation on death, memory, responsibility and survivor’s guilt. In a thematically representative phrase one character says, “There is no way back to the world before the torture. No way back to the world before the massacre.” This is true both historically and psychologically. The Gwangju Uprising, known officially as the Gwangju Democratic Movement, was a pivotal moment in Korean democratization and has come to have totemic significance in Korea culture. Author Han lived in Gwangju until she was nine but moved to Seoul with her family just before the Uprising took place. Paradoxically this move away from the event caused her to focus on it all the more, attempting to find a “way back to the world” that she had left. “Human Acts” describes Dong-ho’s path from the world and the paths of the other narrators as they attempt to navigate it.

Han has done a remarkable job in “Human Acts” by writing a touching tribute to the victims and survivors of the Gwangju Uprising, while also presenting a key moment in modern Korean political history in powerful prose that makes the events comprehensible even to English language readers who might lack historical knowledge of it. “Human Acts” takes its place alongside Choe Yun’s “There a Petal Silently Falls” as one of the must read novels of the Gwangju Uprising.

(Korea Times, 2014-02-14 16:03)

In an era in which it seems that everyone owns a computer, laptop, tablet, or smart phone, sometimes it seems like stodgy old literature might be left in the pre-electronic dust.

The challenge for the Literature Translation Institute (LTI) of Korea is to ensure that even the most digital person in the world can have access to Korean modern literature.

LTI Korea has placed 20 works of early-modern Korean fiction online, where they can be accessed as PDF files or through applications for smartphones, tablets and other mobile Internet devices.

These twenty works are the equivalent of a free collection of modern colonial fiction of Korea that can give an overseas reader a snapshot of the first ”modern” Korean literature and its styles, themes and discontents.

”The authors were chosen carefully to include all aspects of Korean life at the time, from the lives of peasants in villages, to the lives of stifled intellectuals in cities, the stories of the men and women who lived through the colonial era and in the industrialization era,” says LTI Korea President Kim Seong-kon.

.jpg) |

Charles Montgomery lectures at Dongguk University’s Linguistics, Interpretation and Translation Department. / Korea Times |

The works are all from that early era of Korean fiction and the authors include Gang Gyeong-ae, Kim Dong-in, Kim Yu-jeong, Hyun Jin-geon, Kim Nam-cheon, Kim Sa-ryang, Na Do-hyang, Baek Sin-ae, Yi Kwang-su, Yi Sang, Jo Myeong-hui, Chae Man-sik, and Yi Hyo-seok. This could be argued as a veritable ”Who’s Who” of early modern Korean fiction.

Although the stories focus on the same era and difficulties, the works span a wide stylistic range.Kim Yu-jeong’s ”The Golden Bean Patch” is an amusing modern fable with a message somewhere between the worth of a bird in the hand, and the dangers of counting your chickens before they hatch. It is almost a romp.

Yi Sang, on the other hand, one of the fathers of Korean modern literature and first modern Korean writers to incorporate European influences in his work, gives us ”The Child’s Bone” and “Dying Words” (a story which was, in fact, his contemplation of his own upcoming death), two extremely modernist works, which would appear current even.

The themes are similarly varied. Many stories directly address colonialism; a brave thing to do when these stories were written and published. Kim Dong-in’s ”Lashing: Notes from a Prison Journal” is an evocative and tragic tale of an overstuffed colonial prison.

The only way out seems to be by getting sentenced and when a 71 year old man gets sentenced to 90 lashes his cellmates want him to take accept the sentence to lessen, by one, the bodies in the cell.

”Transgressor of the Nation” by Chae Man-sik, is one of the braver of these works, as it attempts to honestly explore the roles and motivations of collaborators.

”Home,” by Hyun Jin-geon begins as a trifle, the random meeting between the narrator and a clown-like man dressed in Korean, Japanese, and Chinese clothes, but the man is revealed have been destroyed by the economic change that has come with colonialism and modernization. This story is a precursor to Cho Se-shui’s ”The Dwarf,” Hwang Sok-yong’s ”The Road to Sampo, ‘’and similar books, and most of these stories can be read as Korean authors taking the first steps towards developing the themes that would inform Korean literature for the next seventy years.

Some of the stories are proto-feminist, with ”Management” by Kim Nam-cheon, exploring the changing roles of women in a changing society, and ”After Beating Your Wife” (with its horribly self-evident title), also by Kim Nam-cheon, revealing the subservient role women were traditionally assigned. ”Bunnyeo” by Yi Hyo-seok is a similarly grim depiction. Poverty by Baek Sin-ae, explores the difficult role given to women, albeit with a more ‘grin and bear’ it approach.

Some stories don’t neatly fit categories, ”The Heat of The Sun,” by Kim Yu-jeong is a brutal story of true love; touching and sad. ”Into the Light” by Kim Sa-ryang considers the meaning of Korean national identity, yet manages to end with a bit of optimism. ”The Water Mill” by Na Do-hyang is a horrific look into ageism and sexism, while Yi Kwang-su (who wrote ”Heartlessness,” known as the first officially ‘modern’ Korean novel) is represented by ”Gasil,” a fairy tale revealing the stupidity of war, who war serves, and the desire of Koreans to return to their hometowns.

Chae Man-sik’s ”Frozen Fish” is, as many of his works, a sardonic look at social relationships in situations of unfair power, and ”Harbin, ‘’ by Yi Hyo-seok is a Yi Sang-ish existential meditation on meaning.

These twenty evocative stories are free, with an emphasis on the “e!” and fans of literature should read them at http://ebook. klti.or. kr/ebooks/m/20century.jsp .

LTI Korea webmaster Park Chanwoo promises these online endeavors will continue.

”Last December Korean novelist Bae Suah’s short story ‘Highway with Green Apples’ was introduced in the ‘Day One’ digital literary journal of Amazon Publishing, and a month later the story was published as an ebook by Amazon with the support of LTI Korea. LTI Korea will continue to make more ebooks available online so that more people can easily enjoy and access Korean literature.”

Fans of Korean literature can only hope so!

(10 Magazine January 2010) In super-annoying ISUU format.

All pictures are mine, as well.

(Los Angeles Review of Books Korea Blog) While the authors mentioned in the last chapter were playing with elements of modernism and post-modernism, others, like Jung Young Moon and Park Min-Gyu, were intentionally distorting, disturbing, and sometimes entirely discarding traditional narratives and techniques. They also, to some extent, abandoned the traditional inward-looking “uri nara” (“our country”) nature of Korean modern literature, finding their stages instead within the individual or in greater world at large. Though often still dealing with entirely Korean issues, the nation-building and didactic nature of the literature that came before is substantially decreased.

Probably the “easiest” of Jung’s works, and the closest to a traditional narrative, Mrs. Brown is relatively linear, with most of the digressions coming during the process of a young couple making prisoners of an older couple. This story of a self-loathing Korean woman with a husband in the United States and two extremely unlikely kidnappers whose purposes are never quite clear ends with an open but slightly optimistic ending — and, compared to Jung’s other works, a positively transparent one.

Mrs. Brown has been released as both a stand-alone novella and as part of the collection A Most Ambiguous Sunday. Jung’s first collection in English was A Chain of Dark Tales which might be seen as spiritual descendant to the yŏnjak sosŏl or “linked novels” of earlier days, each of its 45 stories being a vignette which, in terms of the whole chain, is intended to tell a story. Almost all of them feature damaged characters who mostly operate like partially aware self-automatons. It’s a good book, especially for readers in the United States, to read around the time of Halloween.

This approach is also evident in the A Very Ambiguous Sunday, first published in 2008. Its characters also seem to live lives in conscious dreams, drifting from event to event, remembrance to introspection, and back again. The stories, which in this collection stand alone, are all written with a kind of “cut-and-paste” feeling in which random thoughts, memories, and bits of knowledge of esoterica fight for space in the narrator’s mind. This approach seems to play very well with the postmodernist reader; in Korea, Jung has drawn comparisons to Samuel Beckett.

Park Min-gyu is another of the rising stars of Korean postmodernism, although unlike Jung, Park’s postmodernism is most often found in its content, not in its form. He is an incisive, stylish, superficially offhanded (but with pointed intent) antagonist to modernism, globalism, and the increasing importance of commercial success as the sole judge of success in life. (He also rocks goggles harder than any other writer in history, as pictured above.) Far from pretending that money has no importance, he lampoons how important money has become.

Park’s first two novels, published in 2003, Legend of the World’s Superheroes and The Sammi Superstars’ Last Fan Club won prestigious literary awards, vaulting Park into the official rank of author. His work is often funny, though not in the sense of containing gags or funny wordplay, rather in the unusual, ludicrous, or impossible situations in which his characters often find themselves. Is That So? I’m a Giraffe, is a fairly “normal” modern story (and in fact quite directly “Korean” in the topics on which it touches) until the end, at which point surrealism takes the day. Taking place in an era in which people and their transportation are considered in the same way that a factory might consider how tightly it can package its product into an undersized tin, the book is an undisguised attack on the flaws of capitalism, and Park’s cleverly light writing style allied with his trenchant analysis keeps the reader involved.

This kind of clever writing and analysis continues in Dinner with Buffett, a story based on “real” life, specifically the fact that, each year, one lucky donor wins a “Power Lunch” auction whose prize is a meal with famous capitalist Warren Buffett. As the book begins, Buffett is on his way to to meet the years the auction winner when he is called, mysteriously and urgently, to meet with the president instead. There Buffett is informed of a threat to society from an unidentified “they” who care neither about money nor the status it brings.

After a quick flight back from Washington, Buffett does eventually dine with the young Korean man who won the auction by spending all the money he has won in a lottery. He suggests that money means nothing to him, and that is why he has spent it all bidding on this dinner with Buffett. What’s more the young man arrives having already eaten fast food and without interested in the gourmet meal served. This basis of this existential young man’s life apparently does not include the importance of commodities, or anything attractive only because of its absurd expense.

Castella is an absurdist tale of an alienated youth and his relationship to his noisy refrigerator, a refrigerator that turns out to have some rather remarkable features. As the world quite literally begins to disappear from outside the narrator’s door, the refrigerator performs a remarkable transformative act that can be read as either destructive or as emblematic of the cycle of all things. Park utilizes odd comparisons (refrigerator as football hooligan, refrigerator as friend), includes a short history of refrigeration itself, and in a perfectly matter-of-fact text leads his reader to the story’s surreal yet satisfying — and almost literally “tasty” — end.

Pavane for a Dead Princess explores social expectations in a brilliant style, with Park writing a long, leisurely attack on the commodification of beauty in Korean society (and by extension, the world). In Korea appearance is among the most important commodities one can possess, and until this just year, the first thing you needed when applying for a job was a (Photoshopped) picture of your face. Cracking and grinding at this norm, with broken timelines and a “director’s cut” of an ending straight out of postmodernist cinema, the book tells the slowly but inexorably moving love story of the son of a movie-star and his extremely unattractive girlfriend (whom the narrator describes as “the world’s ugliest woman”). Park uses the extremely superficial nature of society’s reaction to the affair as a position from which to assess the of values of Korea and the whole modern world and find them wanting in humanity.

Park Hyoung-su’s Arpan begins with an amazing feint: a newly successful Korean author remembers his time in the tribal land of Waka, and how he finally found a way to fit into Wakan culture while also unearthing the last Wakan “writer.” That Wakan author, named Arpan, is considered slightly off-kilter even in his own tribe, and when he visits Seoul for a book fair he endures roundly dismissive treatment from the Korean audience. After his talk, Arpan sells seven copies of his handwritten (!) work, while the Korean author, though ostensibly a mere host, signs copies of his own book up to the point of wrist failure. But underneath the Korean’s story lies a secret, one relating to the definition of plagiarism, of respect for a previous author, and of the relationship between creativity, cross-pollination, and cultural appropriation. Though short, the book tackles cultural relationships from several angles, but perhaps the most perplexing and interesting one is posed by the final stance of the Wakan author, well aware of the story’s central secret and prepared with a most surprising response to it.

Other authors have taken up completely modernist structures, including Yi In-seong, whose On You includes an extended conversation with the imagined reader. This concept of the reader-writer interface and the meaning it creates is actually the main point of the novel. Yi’s postmodern approaches include issuing commands from author to reader, speculations as to whom the reader is, and long passages attempting to determine how consciousness relates to text for author and reader both. Enjoyment of Yi’s work depends on one’s feelings about words like “problematizing” and phrases such as “neither unifies or untangles” and “I-centric understanding of the literary object itself.”

Even religion became grist for the post-modern mill, with Judas serving as the elaborately uncertain narrator of Park Sang-ryoong’s Akeldama, which looks back at the violence- and hallucination-laced story of Judas’ last days. Strung through like most of Park’s work with acts of physical and sexual abomination, the story ends in an intentionally ambiguous manner and can be read either as the hope — and perhaps promise — of a new day rising, or as a portrayal of the flamboyant power of death and decay.

The final “postmodern” touch in Korean fiction has been the erasure of borders, stretching Korean literature to encompass all aspects of globalization, an achievement that will be the topic of the next chapter.

(The Korea Times) Recently, the Korean Tourism Organization (KTO) launched a Web-based advertising campaign featuring the “Korea, Sparkling Widget.

” A “widget” is a small Internet-based application that can be attached to a blog or web page where it broadcasts information to all who view the sites. According to the KTO website, the Korea, Sparkling Widget provides “a variety of information about Korea including updates on travel destinations, culture, history, daily life, shopping and more.

The widget will also provide Korean news and article updates through an RSS function, along with a clock and weather function, helping you learn everything you need to know about Korea. Now everyone will have the chance to experience Korea through the Korea Sparkling Widget.

Unfortunately, while the creation of such a widget, and the semi-viral campaign (using college students) to spread it were good ideas, the widget itself, and the target Web sites chosen for the widget, do not seem as well thought out. In fact, both seem to have been imagined in a vacuum, or certainly someplace where foreigners, the alleged target audience, were not given much, if any, input. This is clear both in the content of the widget and how it is being disseminated on the Web.

The widget alternates information about Korea (a good idea) with a series of randomly displayed animated vignettes. I watched the widget for 20 minutes and was staggered by what I saw. The widget, putatively designed to intrigue foreigners, in fact presents them as dangerous and stupid boors, demonstrating that if they visit Korea, they will act like complete rubes, be laughed at by Koreans, be beaten and/or killed, and eat things that will make their heads explode into flames.

I watched some 24 vignettes during my viewing, and in 17 of them, Dave, the foreigner, was represented as a dangerous idiot who brings danger and shame wherever he goes. In one case he kicks a Korean in the testicles, in another he falls off of a ladder while hanging lanterns, is hit with a stick and pierced by an arrow and shocks an entire family of Koreans by entering their house with his shoes still on.

These are not messages that would appeal to any potential tourist. Rather, they paint Korea as a dangerous place full of potential social pitfalls. It’s possible that these vignettes are meant to be humorous. If so, it’s another mistake. How many countries with more successful culture-tourism campaigns use Three Stooges-type humor for self-promotion?

Few, if any.

The campaign to spread and popularize the widget also seems at least partially misguided. College students are contacting Internet users who maintain websites and blogs relating to Korea and Korean culture and asking these Internet users to place the widget on their sites. Even if 100 percent successful, it represents a case of preaching to the choir.

The administrators of these websites are, largely, already in Korea and already know and love the country. Similarly, the people who visit their websites are already aware of Korea. Thus, seeking placement of the widget on these sites seems unlikely to have much impact outside of Korea. It would seem more useful to attempt to place the widgets (after content re-design) on more international sites, such as those of travel agents, general travel blogs, or cultural sites.

The good news is that this represents an opportunity for the KTO. The initial idea was a good one. Creating a useful and interesting widget, and spreading it through a partially viral marketing campaign, was an inspired idea. Unfortunately, the widget as currently designed is unproductive, perhaps even destructive, and the target locations chosen for it do not seem chosen to maximize impact.

I hope that the KTO will go back to the drawing board on the widget, and this time involve some input from members of the target audience, perhaps even involving the same bloggers the KTO has targeted as potential hosts of it. The widget itself needs new content and the effort to place it on websites needs to be re-aimed.

There are many interesting and beautiful features of Korea that could be presented by it. Additionally, Koreans can be quite friendly and hospitable. It is these kinds of elements that Korea should put at the front and center of its culture-tourism marketing, not poorly-animated slapstick demonstrating what goes wrong when cultures collide.

Toggle Content